I conceive of the creative process as a wave, a series of crests and troughs. The fertile upslope is indicative of possession by a duende, but is invariably followed by a usually unproductive, even terrible downslope. This representation accurately describes my painting activity, but isn't applicable to my writing. Writing, for me, rarely involves a duende. Lately, I've come to think of my lexicographic compulsion as a candiru (Vandellia cirrhosa), the tiny, Amazonian fish species infamous for swimming up the anus, vagina, or urethra, wherein it erects spines to hold it in place while it enjoys a hearty blood meal. (Yeah, ouch. In fact, the candiru is one of a very few vertebrate parasites that targets humans.)

Each of the four shows reviewed below "stuck" with me, demanding ink or, in my case, keyboard. I've been planning to write about two of these exhibitions for several weeks, but one or another shiny, neat thing caught my eye and off I went, galloping clumsy in pursuit. The longer I ignore the writing impulse, though, the more the candiru's spines dig in, insistent and maddening. By broadcasting the thoughts I can temporarily rid myself of the fish, and it is with great relief that I finally get this bunch of reviews "out."

+++++

New York Center for Arts and Media Studies: NYCAMS, the physical manifestation of a course credit program affiliated with Bethel University, a mid-sized school located in St. Paul, Minnesota, occupies a stunning, seventh floor space not far from the Flatiron District. Judging by what I read online and my visit to "Paramnesiac Landscape," the group exhibition currently on display in the gallery area, the nascent program is already noteworthy.

I'm a sucker for the show's clever title. "Paramnesia" is defined by Webster's New World Dictionary as a "distortion of memory with confusion of fact and fantasy" or the "same as deja-vu." The exhibition's curator, Robin Reisenfeld, selected the nine participating artists because each "create[s] imaginary landscape worlds through the interplay of memory, fantasy, and recent scientific trends." With the recent art world brouhaha over the role of curators - are they artists, orchestrators, or what? - Reisenfeld's thematic selection may appear too tidy for some folks, but it works well enough. All the work in the show is good, but standouts are Daniel Zeller's drawings and paintings by Sarah Trigg and Cristi Rinklin.

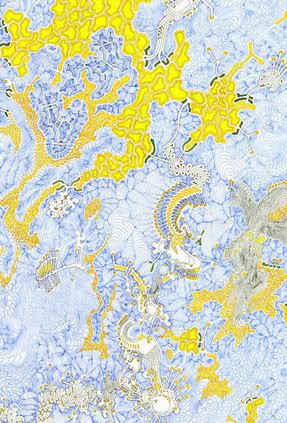

Daniel Zeller

"Skim Level" (detail)

Ink on paper

Zeller's work has generated a fair amount of ink in the past couple of years, deservedly so. His fine line drawings represent the best of two contemporary art world trends: obsessive drawing and pseudo-science. On hand at NYCAMS are four of his fantastic, topographic renderings. "Resistance Factor," a small ink and acrylic work, is quite handsome, suggestive of internal workings - a mapping of capillaries, perhaps - but also of pipelines on the color-coded mish-mash that is a United States Geological Survey chart. Across the room, "Remedial Disfunction," one of the largest wall-works in the show, at 44 x 54 inches, is also one of the best. Comprised almost entirely of punctuated pencil marks, the resulting image can "be" many things. Initially, I understood the drawing to be an aerial view of crop circles but, within moments, I dismissed that association. This landscape is ambivalent, at once exploited and in some state of repair; are we looking at the beginnings of resource extraction or delicate sutures on some undefined organ? It doesn't matter. Such interpretive vacillations are accurately described by Reisenfeld as "conflating the microscopic with the telescopic" and "explor[ing] the confluence of shifting realities and multiple levels of spatial and temporal stratums." (Note: Unfortunately, the works described were not available for reproduction. I've pictured another of Zeller's works above. Due to their detail, the web is unable to do them justice. It's a shame.)

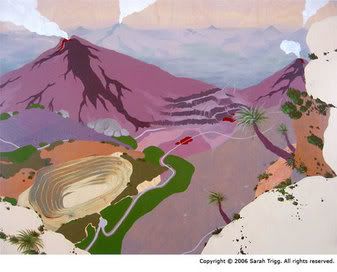

Sarah Trigg

"Unintended Sculptures with Natural Disasters"

2006

Acrylic on Panel

30 x 40 inches

Less ambiguous, but no less preoccupied with the connection of interior to exterior, are the paintings of Sarah Trigg. I was most drawn to "Unintended Sculptures with Natural Disasters," a medium-sized picture that depicts an active, tectonic landscape. Trigg describes her work as "a biopsy," and this recent painting, a combination of aerial survey and traditional, "window" perspective, is bioptic, indeed. Like scientific figures published in a research journal, Trigg's paintings represent the support or data of an ongoing investigation. In fact, I think of her work as geologic dermatology. Standing in front of "Unintended Sculptures with Natural Disasters," I admire the pores and pustules of a vast and violent panorama. Viewing geology in this light effectively humanizes, or at least anthropomorphizes, that which otherwise remains difficult to fathom. Aiding this proportional shift is the combination of formations (and deformations) that Trigg corrals. By depicting so much dynamism in a relatively small area, she presents the viewer with a condensed time frame, millions of years of seismic activity caught in a frozen time lapse, a blink of the geologic eye rather than the human. That Trigg achieves this push-pull dynamic without painting more ambiguous imagery is unusual, and laudable.

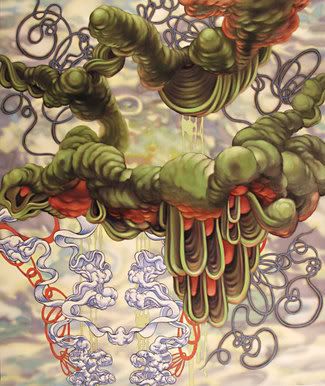

Cristi Rinklin

"Apparition"

2006

Acrylic and Oil on Dibond

36 x 30 inches

Cristi Rinklin's paintings belong to a related, but distinct genealogy. Rather than chart or map her subject matter, Rinklin aestheticizes it. Although her imagery could belong to the "without" - some of her densely layered, colorful forms recall Hubble telescope photographs of distant celestial bodies and events - it feels more inspired by worlds "within." Occasionally, Rinklin even includes a red curtain or some heavy fabric, leading viewers to believe we are looking behind or under - in other words, inward - to discover further mystery and wonder. Rinklin's structures - ornate and organic - are almost Gothic in nature, but also indebted to graffiti and cartooning. I get the feeling she admires these out-lying genres from a critical distance, though, and I'm tempted to describe Rinklin as a younger, more current sibling of Phillip Taaffe and Ross Bleckner. (Note: The two paintings Rinklin included in the the NYCAMS exhibition, one of which is pictured above, were promising, but I wasn't really sold until I visited her website.)

+++++

Fernanda Brunet

"LAAL-LA"

2006

Acrylic on linen

39.37 x 31.5 inches

Galeria Ramis Barquet: The work of Fernanda Brunet is undistinguished. Her paintings belong to the now ubiquitous and often sexy super-flat aesthetic, but her floral explosions are so imminently digestable that, like fast food, viewers are apt to consume and forget. Perhaps aware of this, Brunet has expanded her studio practice. For her most recent solo effort at Galeria Ramis Barquet, "Happymania," she has included a number of bulbous fiberglass sculptures. Occupying the gallery's main space, these forms resemble melting mushrooms and are covered with flowers of varying sizes and colors. "Off the wall" they may be, but they suffer the same fate as Brunet's paintings. (That said, it occurred to me that the sculptures would make great props in an uber-hip clothing store...for a month or so, anyway. To sell to hipsters, you've got to "keep it fresh.")

Brunet's artwork aside, however, a line in the gallery's press release caught my eye. "The artist has also incorporated typical Mexican kitsch decorative elements, such as pastel flowers made out of bread filling." Reading the sentence, I stumbled over the writer's use of "Mexican kitsch." In 2006, assigning specific examples of kitsch to one or another culture approaches meaninglessness. Those rare holdouts not already absorbed into the global pastiche - and pastel flowers made of filling do not qualify - will soon be discovered by the All-Seeing Eye. As a result, identifying the provenance of a kitsch element is a matter of cultural anthropology, useful only if the artist's intent is reclamation.

+++++

The Arsenal Gallery In Central Park: Somehow, I didn't know about this "gallery." (It's more of an open, institutional common room, crowded with cafeteria-like tables and surrounded by offices.) Given my love of all things natural history, I'm thrilled to learn of it, even belatedly. As the press release for "Rare Specimen: The Natural History Museum Show" explains, "the historic Arsenal building...was the first home of the American Museum of Natural History, from 1869 to 1877, before it moved to its current home on Manhattan's Upper West Side." (Happily, after poking about the Internets, I've learned that the NYC Department of Parks & Recreation accepts exhibition proposals. To that, I can only say, "WaWa WeWa!")

"Rare Specimen," curated by Clare Weiss, is an odd, almost arbitrary mix of nine artists, linked by a very general interest in natural history. For example, Mark Dion's "Cabinet of Curiosity" studies and Nicole Tschampel's brontosaurus project offer commentary on scientific subjectivity and the human desire to classify, while Karin Weiner's prosaic collages and Steve Mumford's oil painting of sleeping bears are more straightforward odes to the natural world. Eclectic exhibitions are fun, though, and this one coasts along well enough. "Rare Specimen" does, however, suffer for want of better examples of each artist's work; the show is filled with second-class citizens. "Bears," for example. is a good-looking painting, but alongside many of Mumford's other works, it leaves something to be desired. Other lesser works by established artists are on hand. Walton Ford's "Bangalore" etching is fine, but not outstanding - for the record, I still covet Ford's work, etching or otherwise, but barring an introduction and trade, this ain't in the cards - and Alexis Rockman's large "Hudson River" oil painting has outgrown the brush stroke - it falls apart at any distance. As a result, two of the lesser known artists steal the show.

Emilie Clark

"untitled (MT-P37)"

2005

Watercolor on paper

15 x 11 inches

Emilie Clark's work first appeared on my radar about a year ago. I wasn't sure what I thought of it, but after spending time with her small watercolors at the Arsenal, I'm sold. Individually, the pieces are hit-or-miss, but Clark's delicate touch is captivating; looking at the paintings, one senses her admiration for the plants she depicts. This is true even when her limnings flow into abstraction, a function, perhaps, of the medium, but also, seemingly, of her uncommon sincerity. Three works, in particular, are outstanding: "untitled (MT-P2)," "untitled (MT-P30)," and "untitled (MT-P37)," the last of which is pictured above.

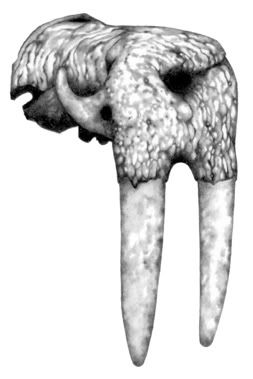

Jeff Hoppa

"Captain Olson I"

2004

Graphite on paper

9 x 12.5 inches

Perhaps the most straightforward work included in the show, Jeff Hoppa's impressive graphite drawings of fossils are based on preliminary sketches he does at the American Museum of Natural History. After he has completed a number of these preparatory renderings, he returns to his studio to create finished drawings. Hoppa names the works after "the specimen's discoverer," but because he uses only his sketches as source material, filling in gaps "creatively," the end product is a mix of careful observation and invention, recalling the early days of natural history. The work - and Hoppa's process - reminds us of how interpretive our knowledge of the world is. Looking at the drawings, I think not just of specimen rooms, anthropology, and paleontology, but also of Albrecht Durer, unicorns, and mermaids. Hoppa's craft is well-honed and the results are beautiful. I'm happy to have made the works' acquaintance.

Jeff Hoppa

"C. H. Sternberg I"

2004

Graphite on paper

12.5 x 9 inches

+++++

Simen Johan

"untitled #136"

2005

C-Print

Yossi Milo Gallery: I make a habit of filling small, hardcover sketchbooks with notes, cut-out images, and selected writings. Every year or so, I exhaust the available space in one of these "commonplace books" and begin another. Because so much tape and glue is used, the finished books sometimes burst at the seams. I often return to swollen, earlier collections when I feel like taking a "thinking ramble." One two-page spread might feature several quotations from an article about politics, more from an article on conservation, and the closing paragraph of a novel, along with random images from art magazines and a graffiti scribble of my own. These apparently arbitrary arrangements lead to unexpected, curious associations (good grist for the mill), but they also offer a trip down memory lane. What was I reading or preoccupied by six years ago? What themes recur year after year?

Simen Johan

"untitled #86"

2000-2001

C-Print

44 x 44 inches

One of these sketchbooks features a stunning photograph on the inside cover, positioned just beneath a lovely Edward Hoagland quotation about the miracle of decomposition. In the picture, a young boy, bicep bandaged as though he has just been immunized, inquisitively pokes at a pile of compost that is teeming with maggots, centipedes, and, strangely enough, Madagascar hissing cockroaches (Gromphadorhina portentosa). I was immediately drawn to the photo when I came across it in the pages of Harper's Magazine. It captures an essential part of my own early experience; time spent around the compost pile behind my dad's boat garage, contemplating the innumerable invertebrates that made their living there with a mixture of revulsion and fascination. Carelessly, when I cut out the photograph and pasted it in the journal, I failed to note the photographer's name. At the time, the image was important to me, but not the artist.

Simen Johan

"untitled #90"

2000-2001

C-Print

44 x 44 inches

But that's not the end of the story. A year later, another image of a child, this one of a young, wild haired girl playing in the mud, was added to a different journal. At the time, I didn't connect the two images, but I was drawn to them for the same reason. I felt they were pieces of my past, representative of a late 20th century rural upbringing in which death and dirt are as formative as birthday cake and Nintendo. Looking at the images, I felt the variety of melancholy joy that I described recently, the joy found in acceptance "of our inevitable decomposition."

Just last week, I learned that both photographs belong to a series entitled "Evidence of Things Unseen," by the young, Norwegian photographer, Simen Johan. Only four or five years older than me, Johan has produced an impressive number of powerful, digitally-manipulated photographs. His most recent body of work, "Until The Kingdom Comes," is uneven, but includes some work that I respond to viscerally. This series of photographs foregrounds animals rather than children and childhood, appealing to our human longing for connections vanquished or ignored. I spent a long while with the large prints at Yossi Milo Gallery. Although the pictures work better with my glasses off - a function of my being too aware of the digital manipulation otherwise - the images are more emotionally resonant than most of what is on offer in Chelsea these days. Johan is one step ahead of the digital photography pack.

Photo credit: Candiru line drawing via Queensland Department of Primary Industries website (uncredited); Daniel Zeller/Cristi Rinklin images, courtesy the respective artists and Robin Reisenfeld; Sarah Trigg image, courtesy the artist; Emilie Clark image, courtesy Artnet.com; Jeff Hoopa images via the artist's website; all Simen Johan images via the artist's website